Rather than try to come up with some soul-stirring message for Memorial Day, I’m going to turn instead to former President Abraham Lincoln in his eloquent letter to Lydia Bixby during the Civil War:

Executive Mansion,

Washington, Nov. 21, 1864.

Dear Madam,

I have been shown in the files of the War Department a statement of the Adjutant General of Massachusetts that you are the mother of five sons who have died gloriously on the field of battle.

I feel how weak and fruitless must be any words of mine which should attempt to beguile you from the grief of a loss so overwhelming. But I cannot refrain from tendering to you the consolation that may be found in the thanks of the Republic they died to save.

I pray that our Heavenly Father may assuage the anguish of your bereavement, and leave you only the cherished memory of the loved and lost, and the solemn pride that must be yours to have laid so costly a sacrifice upon the altar of Freedom.

Yours, very sincerely and respectfully,

A. Lincoln.

Mrs. Bixby.

No President was greater than Lincoln in digging deep into the human soul to find the words that encapsulate the emotions of loss during the darkest days of our country.

Unfortunately, the “Bixby Letter” as it has come to be known, is actually Lincoln falling victim to what was likely a scam. Lydia Bixby certainly had five sons that fought for Union forces, but there is confirmation that only three had died by the time Lincoln wrote to her. Historians also believe that one of the sons may have defected and joined the Confederacy. Bixby came to light only after applying for military pensions on behalf of all five sons, claiming they were all dead.

The “Bixby Letter” came back into social awareness thanks to the movie Saving Private Ryan, where General George Marshall is made aware of three brothers that had all recently been killed. He reads the letter (with some updated language) to his subordinates and puts into motion the fictional mission to save the 4th brother–Private Ryan (it’s one of about 10 scenes in that movie that still get me choked up). Before that scene, a pool of women typing World War II death notices is shown, preparing the letters that would be delivered to mothers who had lost sons like Mrs Bixby–but not as eloquently as President Lincoln had written.

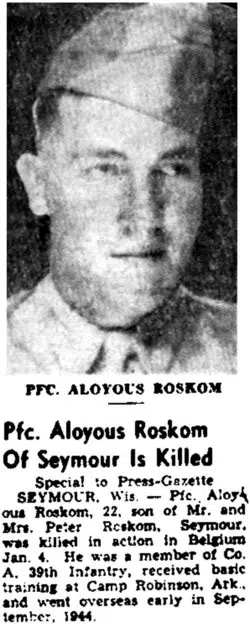

My maternal great-grandmother, Anna Roskom, got one of those letters. Her son, Aloyous (who was called Loy as a child) was killed in action on January 4th of 1945 in the forest of the Ardennes while fighting with Company A of the 39th infantry during the Battle of the Bulge. He had been in the service for just four months before he died. He remains buried there. He was just 22-years old.

That is all that I know about his death. His parents were quite old when I was a child, and I never heard them talk about him. I didn’t even know my grandfather had a brother that was killed in the war until I had to do a family tree for a class assignment in grade school.

I regret that I never have found out more about Loy. I never asked my grandfather what he remembered about him. My grandfather was older than him, but could not serve in the war due to health issues. Now Aloyous is nothing more than a black and white photo posted with his obituary in the Green Bay Press Gazette that I came across a few years ago during an internet search.

But I wonder, whatever happened to that letter? Did Anna keep it, tucked away in a box with other mementos of her lost son? Is it in another box that some other distant relative has stored away in a basement on a shelf, for their children to find and wonder why it had been kept? Or did Anna throw the letter away–not wanting a physical reminder of that loss?

This Memorial Day let’s think of those like Mrs Bixby’s sons, and Anna Roskom’s son, who both laid such a costly sacrifice upon the altar of freedom.